Hverfisgallerí, Reykjavik, Iceland. 2019

Found Objects and Lost Time in Sigurður Árni Sigurðsson’s Corrections

Æsa Sigurjónsdóttir.

In 1990, Sigurður Árni found a black-and-white photograph of a dog in a flea market in Sète in the south of France. The strange shadows cast by the dog in the bright sunlight caught the artist´s eye. The photo lay on his desk for a while before he decided to glue it onto a piece of paper and bring the dog back to life, breaking its way out of the frame by creating its strange double he named Found Dog. The image of the dog and its shadows mark the beginning of a series of works which has since been growing and developing under the title Corrections.

The first Corrections were exhibited in Sigurður Árni’s retrospective in Reykjavík Art Museum at Kjarvalsstaðir in 1994. Since then, scores of images hav e been added to the series which now hold around 200 works. The series reflects the artist’s passion for found photographs and postcards which he discovers in flea markets and second-hand bookstores during his travels abroad, particularly in France. It’s probably more accurate to say that the images appear to him during his strolls, like memories which surface when you least expect it. Often, the photographs lie unused with the artist until they find their target. They might even address him and remind him of their existence, like a dog which wanders into the photo frame at the wrong moment. The world turns into a stage in front of the camera, everything that is staged becomes a symbol. Even a dog, minding its own doggy business, becomes an actor when the lens is pointed at it.

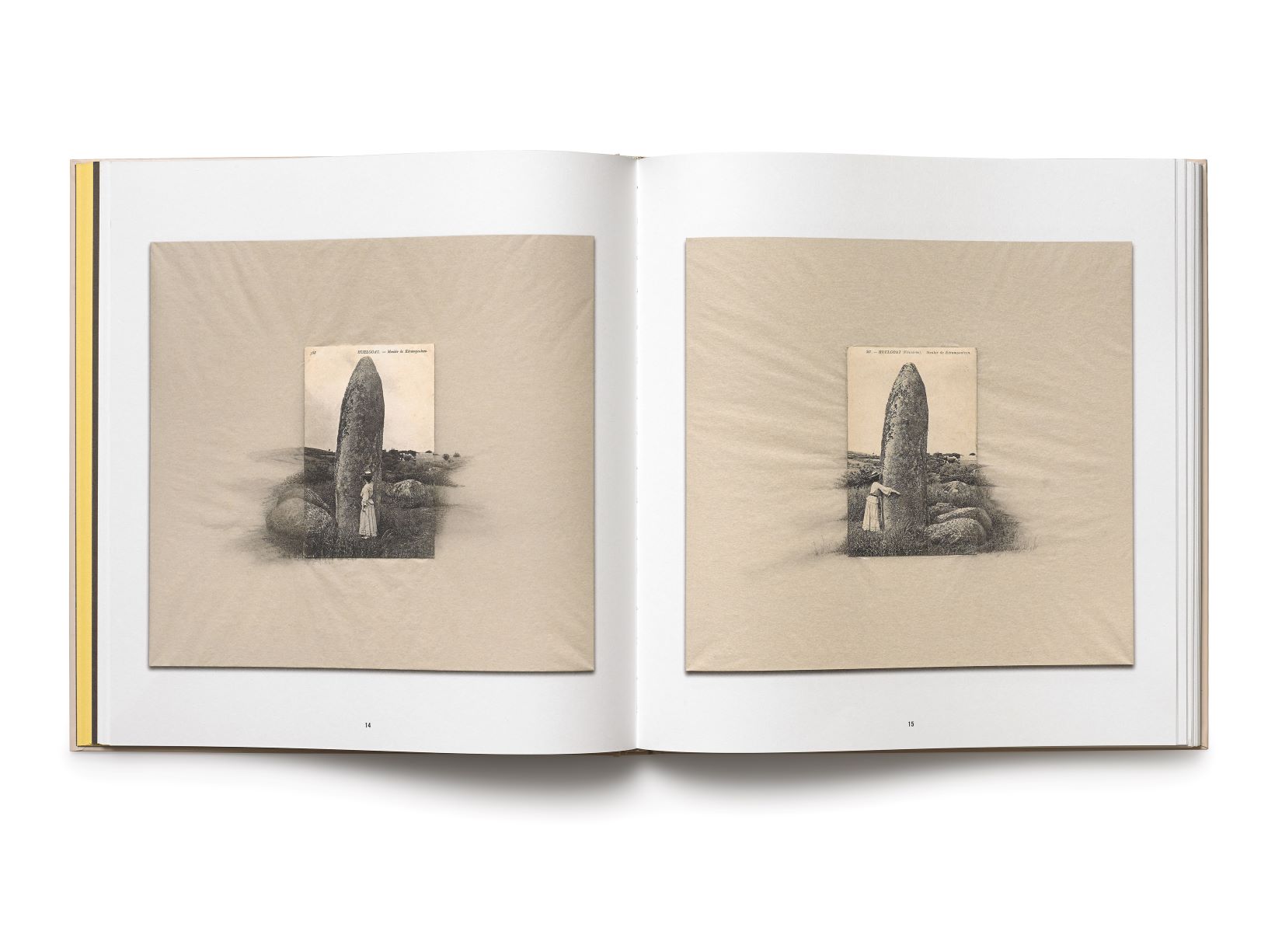

Most of the Corrections are closely connected to French culture, a certain time and place, as is the case with the photograph of cyclist Lance Armstrong, or the exit of the unknown bride and groom. A young woman takes on the role of a Sunday painter where she sits, all dressed up, in a field in front of her easel in the postcard L’artiste et le modèle. Traditional salt mining on a distant sunny shore transforms into a peculiar, geometric landscape or modern landscape – Paysage moderne. Here, each character plays himself. The surroundings are affected by the presence of the French bombshell Brigitte Bardot, who enters eternity as the irresistible BB. The Breton schoolgirls become actors in an erotic landscape series around phallic menhirs. Even an innocent family picnic becomes laughable in the context of a funny French advertisement with the famous Michelin Man.

The cultural history, however, is irrelevant, as this has a different purpose. Sigurður Árni gives titles to some of the images, writes them lightly in pencil at the bottom of the sheet, and the text reflects his personal connection to the subject.

Al though most of the postcards have inscriptions in French, information about time and place are of little matter, after the artist´s interference. Photographs of mundane activities and well-known situations offer various interpretations and improvisations in the artist’s rhetorical play. Haycocks with old-fashioned canvas covers appear as strange, erotic symbols from the past at the farm Svínafell in Öræfi. Three Young Puffins is a pun on an advertisement depicting three blondes in the Blue Lagoon. They are dressed in colourful swimsuits, two in yellow, one in red, and their supple bodies echo the three young puffins with their yellow and red beaks, joining colours and images in an ambiguous tourist symbol and a droll wordplay.

The mind play which Sigurður sets in motion in Corrections, is in many ways reminiscent of the writings of French semiotician Roland Barthes (1915-1980), about the rhetorical function of images, but also of his more personal interpretation of the studium and punctum factors of photographs. The studium characteristics of Corrections are familiar to the viewer: Bride and groom exiting the church, children on a see saw, dog walking in the sun, everybody knows the Leaning Tower of Pisa. Other points pierce the viewers and affect them deeply, activate the imagination or cause a chill, like a bad omen of what is to come. Such effects interrupt the whole, because as Barthes described, punctum is an interruption similar to a sting, speck, cut, a little hole – and also cast of the dice. 1

In this manner, Sigurður disturbs the image when he gently draws on it. By disrupting the frame and extending the image, he not only changes the composition and various details within the image, but also transforms the punctum effects of the photograph and simultaneously it´s status as a photograph, documentation and a narrative. The viewer cannot be sure what is original and what’s been added. Thus, the additions create a new context, they pull the postcards from the past, into the present, where time and place is forgotten or no longer relevant. A dark spot, hole or a throw of the dice can transform each Correction into a scene, independent from its frame. A photograph of an empty gymnasium calls out for some participants, while other pictures which portray children at play stir up an uncanny feeling of what is to come, a foreboding of the familiar situation.

Sigurður Árni’s selection of images might surprise the viewer and it could prove difficult to find the thread that connects the photographs. Each image sparks different speculations and ideas of the characters and items which come alive in Corrections. Some of the images belong to postcard series, others stand alone. Evidently each image also belong to a another and a larger context in the mind of the artist as well as the viewer, where each person creates their own narrative.

Sigurður Árni allows French artist Marcel Duchamp (1887– 1968) to set the stage for the series in the image Mr. Duchien, -with tongue in cheek. The title is a direct quote to the first image in the series, the origin of the work, i.e. Found Dog, which also refers to Sigurður’s dialogue with Duchamp’s famous selfportrait, With My Tongue in My Cheek (1959) where Duchamp extended his own profile, cast in plaster, with gentle pencil lines. With Mr. Duchien, -with tongue in cheek, Sigurður also breaks the principle of Corrections, in that he is not extending a photograph but giving extended life to a found stone (which resembles a dog’s head), he mimics Duchamp’s pun and gives him a gentlemanly nod at the same time.

In a famous lecture on “The Creative Act”, Duchamp defined art as a missing link. He believed art could be found in the space in-between things, rather than in that which is visible. 2 Therefore, it seems safe to claim that the Corrections are a kind of metaphor for art itself and the struggle with creation, for the gap which appears, as Duchamp described it, in the infrathin, in the intervention which is almost imperceptible, in the feeling which Duchamp claimed one could describe but not define, that which appears in the metaphor of oblivion, in the shiny surface of the mirror or in the lingering warmth when you rise from your chair. 3

In her famous article, “In Plato’s Cave”, the U.S critic and author Susan Sontag (1933–2004) made the claim that all photographs are a reminder of death: “To take a photograph is to participate in another person’s (or thing’s) mortality, vulnerability, mutability. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt.” 4 Sigurður Árni’s intervention allows him to loosen these restrictions of the photograph, it thaws and comes alive in the drawing which cuts it loose from the frame. The intervention, the addition, the shadow or the hole which Sigurður adds to the surface takes over and matters more than the original image. The drawing’s friction against the photograph also reminds us that photography has not always been a bearer of truth, as we often claim it is. During the latter half of the 19th century, drawn images were considered more scientific and trustworthy than photos. Even today, a drawing of a plant is believed to be a more exact copy of the real object than a photograph. By combining these two different media in one image, Sigurður Árni erases the time limits, creating artwork which transcends time. In doing so he disarranges the connection between the original and the copy, and transforms Corrections into a metaphor of the art creation itself, within a much larger conceptual context.

As Sigurður Árni himself has said, Corrections play a particular role in his creative process. Although his work is meticulously planned, he starts correcting photographs and postcards to free himself of blockage, get his creativity flowing, a situation which could be likened to a method which the French Surrealist and author André Breton (1896–1966) called automatism. Its purpose was to free the artist from psychological restraints and liberate his imagination. Therefore, the artist’s intervention could be connected to the search for the manifestations of the dream, as was practiced within surreal aesthetics where the subconscious was considered the only true reality. Breton looked to Sigmund Freud’s (1856–1939) theories about the subconscious and hoped to create a new creative thought which would be a direct expression of the unbridled imagination. Therefore, it might be assumed that Sigurður transfers Breton’s questioning about the abolition of the binary oppositions; life and death, past and future, real and imaginary, compatible and incompatible, thus gaining a Surrealist action in the attraction between drawing and photograph. 5 Hence, Corrections are Sigurður’s way to maintain the spark in some kind of a Divine Comedy, where the artist travels alone in No Man’s Land, looking for a partner. The rhetoric of painting and writing has been forgotten by most people and the artist, as well as the viewers, must make do with the echo in Plato’s cave – or maybe we should rather view Corrections as a testimony of the moment when humour forges its way to the surface, in the self-irony which has characterised art from the very first days of found things.

1 Roland Barthes, La chambre claire. Note sur la photographie, Paris: Gallimard, 1980, p. 49.

2 Marcel Duchamp, „The Creative Act,“ Art News, 56:4 (summer 1957), p. 28-29.

3 Marcel Duchamp, Notes, Paris: Flammarion, 1999, p. 21.

4 Susan Sontag, „In Plato‘s Cave,“ On Photography, New York: Anchor Books Doubleday, p. 15.

5 André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism,The University of Michigan Press, 1972.