Listasafnið á Akureyri, Iceland. 2018

Drifting Surfaces

Markús Þór Andrésson, Director of Reykjavik Art Museum.

Through his career, Sigurður Árni Sigurðsson has made countless variations of the painting as a medium and experimented with its possibilities. His experiments have often led him into the realms of space, either with various two-dimentional spectacles or with the creation of three-dimentional objects. The play and interplay of light and shadow is a recurring theme in his work. In a large painting, made especially to celebrate the opening of the Akureyri Museums new showrooms, Sigurður depicts the shadow silhouette of the distinctive windows of the old Dairy Coop, KEA, that used to reside in the building. Light seems to flood in through the long windows, break on the contours of the horizontal windowposts, and fall onto the blank canvas. Albeit, this is a visual deception, the whole scenery is painted, the light as well as the shadows. There is also a real wall between the windows and the painting, so the optical illusion immediately reveals itself. The sunlight, sailing its own course in the actual window-space, is also arrested in a painting in the inner space. What motion is the artist referring to in an exhibition he calls Drifting Surfaces?

Sigurður Árni’s works are filled with contradictions that at first glance seem to be irrelevant, but gradually twist the outcome, so one has to take a closer look. The simple interaction of geometric shapes on blank or painted canvas, in a nameless, blue- and greenish painting, develops a visual illusion. A closer inspection leads one to speculations about the history of painting altogether, and its constant struggle between subject and content. Though a painting is in itself an extremely thin surface, it can portray and hint at every possible width of the physical and imaginary world.

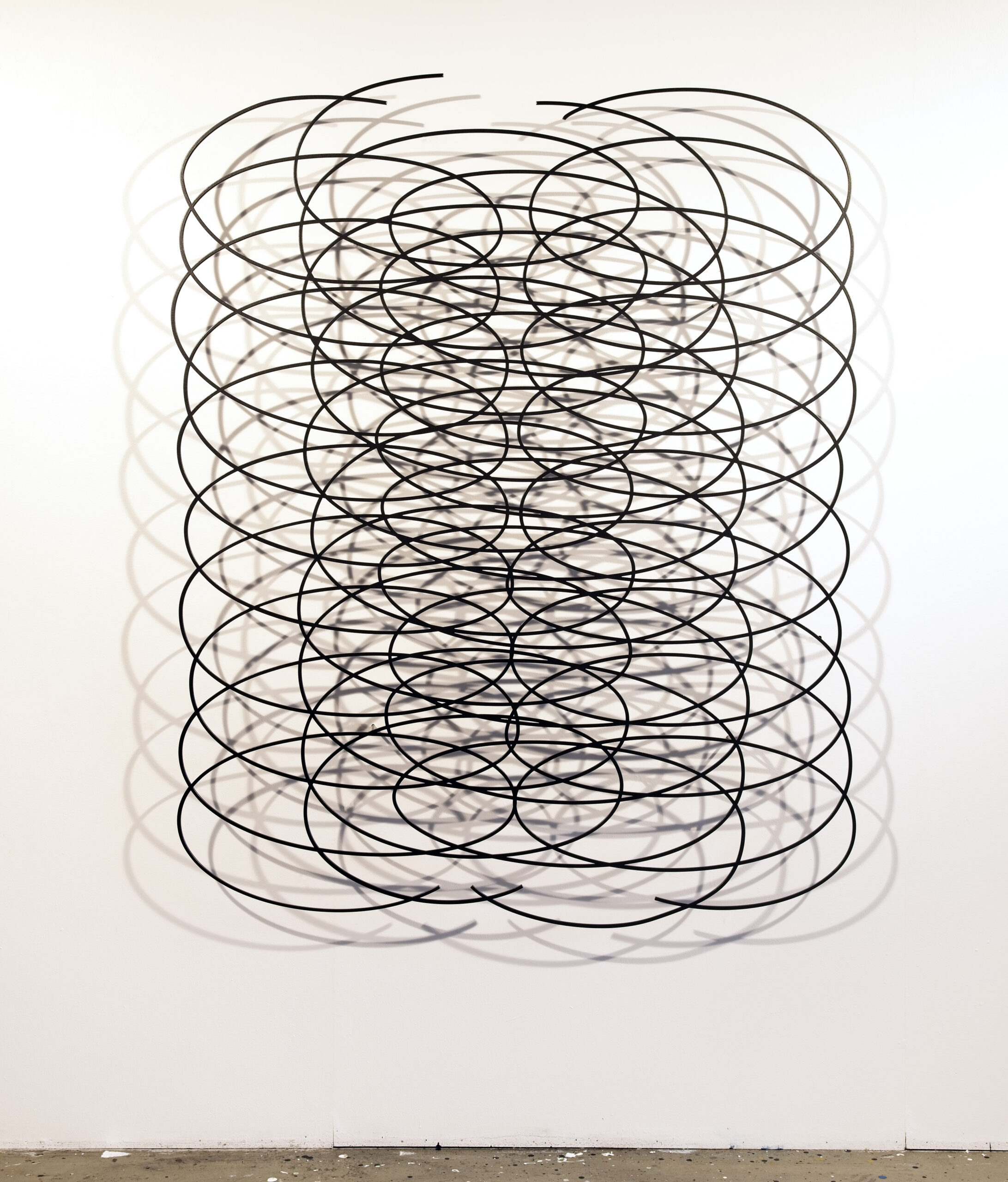

Painting, its tradition and background, are Sigurður’s main subject but he has always used other medium’s as well. In recent years he’s been working on reliefs. The works are carved into aluminum thins, some of which are coloured and lacquered. They are mounted with a surplus space between the works and the wall, so the works cast shadows on it, whether it is daylight or electric light. The shapes are either inter-connected dots reminiscent of molecule diagrams, lines that form polygons waving towards natural forms, or the complex structure of spirals. First and foremost they are an abstract puzzle with dimensions, the gap between the two- and three-dimensional, foreground and background – the borders of a drawing or painting on the one hand, and a sculpture on the other.

At first glance, Sigurður’s reliefs seem to be made out of found material, shapes derived from natural or digital models, cast in a mold and covered in pigment, a process similar to a manufacturing industrial products. A closer look reveals that the framework are abstract drawings by the artist, processed in a way that almost eradicates the human touch. Some of the reliefs are based on Voronoi diagrams; a natural algorythm to be found all around us. The Russian mathematician Georgy Voronoi defined the system in the 19th century: It explains how a plane partitions in the weakest place between two points. This is the form and structure of columnar igneous rock, stone polygons, a giraffe’s pattern etc. Voronoi diagrams are to be found in the smallest particles of substance matter as well as in cosmic dimensions of the universe. The same applies to the spiral, or the helix, presented in Sigurður’s works. It has a similar absolute value found in nature on various scale in the world. Voronoi diagrams and helixes both refer to infinity.

These works arouse a feeling for a vast, limitless space with no actual center or special visual importance. The recurring shapes seem to be able to expand in any direction, without being restrained by a frame or other external borders. This is emphasized by placing them as if floating in the air. The works do not contain a visible order, though they indeed form some kind of a pattern. Familiar ideology comes to mind, on inherent instability of both language and meaning. Late in the twentieth century, scholars started referring to the concept of root systems “rhizomes” and existentialism, instead of center or core. One could say that with these works, Sigurður opens various visual portals into the worlds of materialism and idealism.

Sigurður’s works objectify the idea that man only senses the world in brief glimpses; as parts of a whole or a moment in eternity. Man’s visual area and other senses have their limits, and our sense of things largely relies on our preconception of experience and understanding. Our mind assumes to fill into the gaps of our knowledge of the world, conclude about progress and come up with the most likely and plausible outcome. Sigurður reminds us about this unconscious ability in a simple but incisive way through his works: There’s an invisible line between a painting and the whole world outside of it; we consciously enter the painting’s illusion, yet a similar illusion can apply to all our surroundings. Not only does the artist point out that our perception and knowledge is fallible, but that the world is also prone to constant progress. Concepts such as parameter or constant, neither have the same meaning for two persons who experience the world differently, nor is it ever the same from one moment to the next. Hence, everything is moving, unsteady images, neverending vortex and drifting surfaces.